Living as Others in Japan

Japanese Studies Association of Australia 2011 Biennial Conference

Internationalising Japan: Sport, Culture and Education

University of Melbourne, Melbourne Law School

185 Pelham Street

Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

2011-07-04 through 2011-07-07

Wednesday, 2011-07-06, 11:00-12:30 AEDT (Local Time)

Room 102

This panel will present two historical papers about individuals whose lives were affected by the Pacific War, and a third paper which examines issues involving intercultural communication between Japanese and non-Japanese people. The two historical stories focus on how their respective individuals navigated their life course as “Others” in Japan. Hamilton will shed light on children born to Japanese mothers and Australian fathers during the Allied Occupation in Kure. Tamura’s paper is on a businessman of mixed heritage, English and Japanese, born in Kobe, who was interned in Japan. Parry’s paper provides a look into intercultural communication between Australian students in a homestay among ten Japanese host parents.

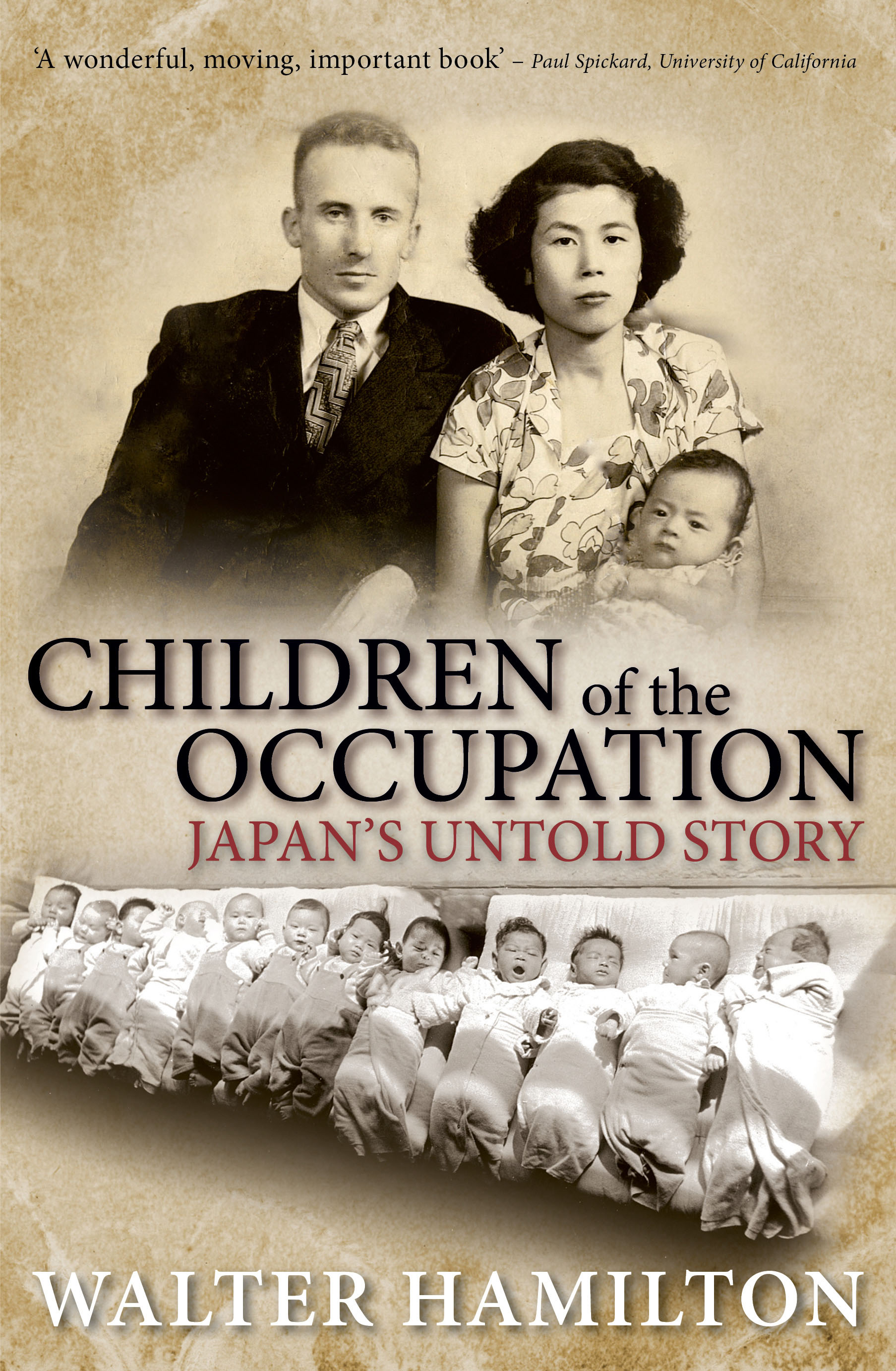

Kure Kids

Walter Hamilton

Walter Hamilton has recently completed a book on the mixed-race children of the Occupation, under the working title of Lest We Beget: The Mixed-Race Legacy of Occupied Japan. (www.lestwebeget.com).

Nearly sixty years have passed since the post-war occupation of Japan. It might be assumed historians will have exhausted all there is to say about its political, economic and social effects. But one unexplored aspect remains vividly alive: the hidden ancestral links that bind Australians, Americans, Britons and others to Japanese blood-relations never known, never met: the unclaimed, mixed-race offspring left in Japan when the troops departed. Their fathers would not or could not acknowledge them: an estimated 10,000 children, including several hundred fathered by Australians.

So familiar is the idea of military conquest leading to the birth of “unwanted” children outside marriage – across racial, class and cultural divides – they tend to be dismissed as a natural corollary of war. Their appearance in occupied Japan came as no surprise. The “Madame Butterfly” tradition provided a high-toned model of Western men exploiting Japanese women. As if their biological inevitability made them what they were, the children attracted scant attention from Western writers, who acquiesced in facile assumptions about their fate. Surely they were disowned by their fathers, lamented by their mothers and thrust to the lower depths of society. The eminent American historian John Dower has called them “one of the sad, unspoken stories” of the occupation. Japanese historical and fictional treatments of the issue also suffer from a determination to link the children exclusively to prostitution, moral collapse and national humiliation.

Australia joined the occupation not expecting to convert the former enemy but to punish and ostracise him. With immigration restrictions, in some respects, even tighter than they were in 1941, permission was denied for troops in Japan to marry across the race divide. Anyone defying the ban risked being forcibly removed from his de facto wife and children. Although these measures were relaxed in 1952 to admit the first Japanese war brides, no such right was extended to the unacknowledged or orphaned children of Australian servicemen. In addition, the federal government maintained an elaborate deception to stop the children being adopted by Australian families. Bogus welfare arguments were used to cover a purely political determination. The moment the strategy showed signs of faltering, it was reinforced through public monies being deployed to keep the children in Japan. There were almost no exceptions, even for the sons and daughters of brave men who had fought and died in the Korean War. In the words of a leading churchman of the day, the Reverend Alan Walker: “There have been few more disgraceful incidents in the whole miserable history of Australia’s racial immigration policy.”

This paper will introduce several individuals born in or near the city of Kure, in Hiroshima prefecture, where the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) was based from 1946 until the withdrawn of the last Korean War contingent in 1956. The Kure Kids encountered discrimination because of their physical appearance, dysfunctional family life, low socioeconomic status and social isolation. But the lives of these Japanese “others” represented much more—in quality, variety and achievement—than is suggested by the conventional portrayal of “sad, unspoken stories.”

Between Father Land and Mother Land: a British-Japanese Dual National and his Pacific War

Keiko Tamua

In war, individuals are categorized either as friend or foe, and enemy nationals are seen and treated with suspicion and fear. In December 1941, when the Pacific War started, about 700 out of 2134 civilians of the Allied nations who were residing in Japan were arrested or interned as enemy aliens. Most of them had lived in Japan for a number of years and had become part of the community. Some civilians were repatriated to their home countries on exchange boats in 1942 and 43, but others decided to remain in Japan even though they knew they were going to be interned or kept under police surveillance. Most of them had mixed heritage through their parents and/or having Japanese spouse; they thought their home was Japan rather than Britain or the USA, and they felt they could not leave without their family members.

F. M. Jonas was one of these expatriates who were caught in the war. He was born in Osaka in 1878, having a British father and a Japanese mother. He had established himself as a respectable British businessman in pre-war Kobe, running a stevedore business at the port. He was highly regarded both in the expatriate and Japanese communities, having been vicechairman of the Kobe Foreign Chamber of Commerce, and president of the Kobe Regatta and Athletic Club – the premier expatriate social club in Kobe. When the war started Jonas was arrested by the Japanese authorities, and later interned as an enemy alien. However, he managed to secure release from internment through British-Japanese dual citizenship, and he changed his name to Morii Kamejirō. When the war ended, he tried to re-establish his formal status as a British national. He died in 1950 before final resolution was officially made. Did he claim citizenship of convenience to suit the circumstances, to avoid internment, and consequently did he betray his father land? Or did he have legitimate reasons to do so? What were the consequences of his action for himself and his family? Japanese nationality laws upheld the principle of paternal succession until 1985, and dual citizenship has never been recognized. How did Jonas convince the authorities of his dual nationality? In this paper, I will discuss the life course of F. M. Jonas, who lived between father land and mother land in the middle of the Pacific War. Through Jonas’ story, I will explore, from a historical point of view, how the nationality of mixed decent people has been interpreted and handled in Japan and Britain.

For more information, click here.