Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude EatonPosted in Anthologies, Asian Diaspora, Books, Canada, Caribbean/Latin America, Media Archive, United States, Women on 2017-09-06 03:43Z by Steven |

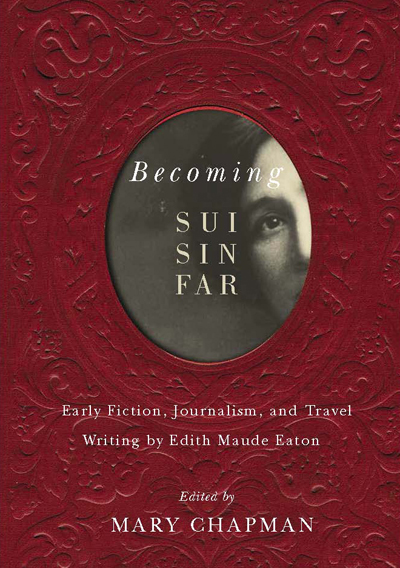

Becoming Sui Sin Far: Early Fiction, Journalism, and Travel Writing by Edith Maude Eaton

McGill-Queen’s University Press

July 2016

352 pages

6 x 9

ISBN: 9780773547223

Edited by:

Mary Chapman, Professor of English

University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Newly discovered works by one of the earliest Asian North American writers.

When her 1912 story collection, Mrs. Spring Fragrance, was rescued from obscurity in the 1990s, scholars were quick to celebrate Sui Sin Far as a pioneering chronicler of Asian American Chinatowns. Newly discovered works, however, reveal that Edith Eaton (1865-1914) published on a wide variety of subjects—and under numerous pseudonyms—in Canada and Jamaica for a decade before she began writing Chinatown fiction signed “Sui Sin Far” for US magazines. Born in England to a Chinese mother and a British father, and raised in Montreal, Edith Eaton is a complex transnational writer whose expanded oeuvre demands reconsideration.

Becoming Sui Sin Far collects and contextualizes seventy of Eaton’s early works, most of which have not been republished since they first appeared in turn-of-the-century periodicals. These works of fiction and journalism, in diverse styles and from a variety of perspectives, document Eaton’s early career as a short story writer, “stunt-girl” journalist, ethnographer, political commentator, and travel writer. Showcasing her playful humour, savage wit, and deep sympathy, the texts included in this volume assert a significant place for Eaton in North American literary history. Mary Chapman’s introduction provides an insightful and readable overview of Eaton’s transnational career. The volume also includes an expanded bibliography that lists over two hundred and sixty works attributed to Eaton, a detailed biographical timeline, and a newly discovered interview with Eaton from the year in which she first adopted the orientalist pseudonym for which she is best known.

Becoming Sui Sin Far significantly expands our understanding of the themes and topics that defined Eaton’s oeuvre and will interest scholars and students of Canadian, American, Asian North American, and ethnic literatures and history.