Mulata Nation: Visualizing Race and Gender in Cuba by Alison Fraunhar (review)Posted in Articles, Book/Video Reviews, Caribbean/Latin America, Literary/Artistic Criticism, Media Archive, Women on 2019-11-03 03:21Z by Steven |

Mulata Nation: Visualizing Race and Gender in Cuba by Alison Fraunhar (review)

The Americas

Volume 76, Number 4, October 2019

pages 727-728

Mey-Yen Moriuchi, Assistant Professor of Art History

LaSalle University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

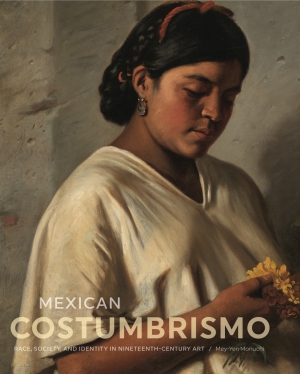

Mulata Nation: Visualizing Race and Gender in Cuba. By Alison Fraunhar. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2018. Pp. 262. $70.00. Cloth.

Alison Fraunhar discerningly examines how the mulata has been represented and performed in Cuban visual culture from the nineteenth century to the present. She analyzes a variety of visual media, from prints and paintings to film and photography, to demonstrate how the identity and stereotypes of the mulata developed within popular culture and the national imagination.

Considered a bridge between European subject and African other, the mulata was “European enough to be visible and beautiful to the white male subject, and African enough to be typologized as sexual, primitive, desirable, and available” (4). Invoking Antonio Benítez-Rojo’s notion of “The Repeating Island,” Homi Bhabha’s concept of colonial mimicry, Stuart Hall’s model of identity based on ambivalence, and Judith Butler’s performativity of identity, along with the work of other theorists, Fraunhar investigates how performance and representation of the mulata and mulataje (performativity of the mulata) are intertwined. The study is not focused on actual life experiences of mulatas but rather their visual representation across media.

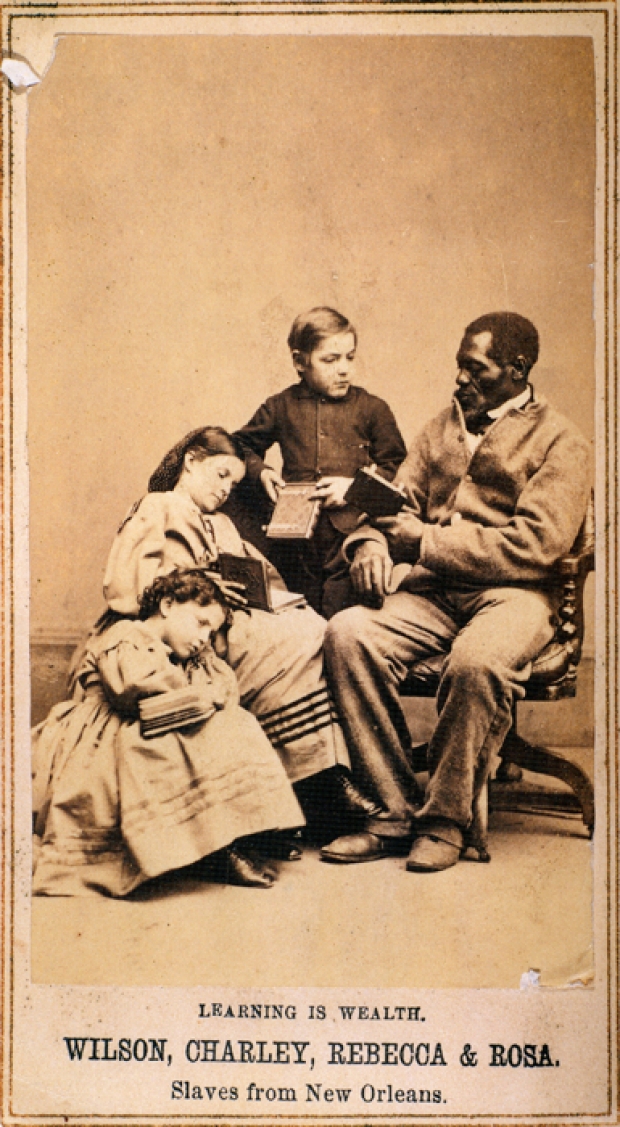

Fraunhar begins her analysis through the lens of costumbrismo, a literary and artistic movement popular in Spain and the Americas that represented scenes and types from everyday life. The figure of the desirable mulata, though in existence since the seventeenth century, was cemented during the nineteenth century with costumbrismo. An interesting manifestation of this occurs in marquillas cigarreras, small chromolithographed papers in which cigarettes for the Cuban domestic market were bundled. In this fascinating medium, Fraunhar shows how marquillas served as sites of cubanidad (Cuban identity). Fraunhar argues that the images of mulatas on marquillas demonstrate colonial anxiety and the inability to clearly define racial, social, and spatial boundaries. Unfortunately, the images presented in this chapter were all misnumbered, disrupting the fluidity of the text.

Chapter 2 focuses on the performance of the mulata on the stages, dances, and streets of nineteenth-century Cuba. In popular theater, like teatro bufo and zarzuela, the mulata was one of several principal stock characters performed, along with the negrito (black boy) and the gallego (Spaniard). During this time, the connection between prostitution and mulataje became explicit, thus producing tension between the mulata as a symbol of the nation and desire. Several Cuban actresses found success outside of Cuba in Mexican cabaretera films, performing cultural and racial passing.

Chapter 3 considers the mulata as a sign of femininity, cosmopolitanism, and modernity. Fraunhar examines how the mulata was variously depicted on magazine covers and in avant-garde paintings by early twentieth-century artists such as Jaime Valls, Mario Carreño, Carlos Enríquez, and José Hurtado de Mendoza. Although an icon of modernity, representations of the mulata were still rooted in past tropes of desire and availability. After the revolution of 1959, women’s roles in society were debated as leaders struggled to redefine the nation.

In Chapter 4, Fraunhar investigates how the revolution sought to reform the mulata as a revolutionary citizen. Several Cuban films produced in the 1960s and 1970s have mulata protagonists, presented to showcase how Cuban revolutionary society was constructed upon utopian ideas of equality and community. The mulata became the “new (wo)man” of the revolution (157).

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 and the beginning of the Período Especial, cultural production was disrupted, and economic crisis ensued. Cuba now positioned itself to foreign visitors as an exotic, nostalgic, tropical tourist destination. Mulatas resumed the role of the sensual, the desirable, and available body of the nation. The rise of jineterismo (hustling) and prostitution associated with the mulata became ubiquitous in Cuba in the 1990s, as did the emergence of drag and cross-gender performativity.

In Chapter 5, Fraunhar discusses the work of several photographers who capture the plight and agency of these mulata jinetera, gay, and trans performers.

A strength of this study is the wide range of popular visual culture that is included, though at times this means less in-depth analysis of specific…

Read or purchase the article here.