How Anti-Chinese Propaganda Helped Fuel the Creation of Mestizo Identity in MexicoPosted in Articles, Asian Diaspora, Caribbean/Latin America, History, Interviews, Media Archive, Mexico on 2017-11-27 01:56Z by Steven |

How Anti-Chinese Propaganda Helped Fuel the Creation of Mestizo Identity in Mexico

Remezcla

2017-06-13

Freddy Martinez

Brooklyn, New York

Chinese Mexican pilgrims march to the Basilica de Guadalupe, Mexico’s holiest shrine. Courtesy of Pilar Chen Chi. |

Like most revolutions, the one Mexico fought at the beginning of the 20th century was brutal. Over a million people, both civilian and revolutionaries alike, died in the span of ten years. And although, by its end, a new constitution guaranteeing indigenous civil rights was enacted, life was still no better: assassination, disease, and violence left the Mexican state nearly ruined.

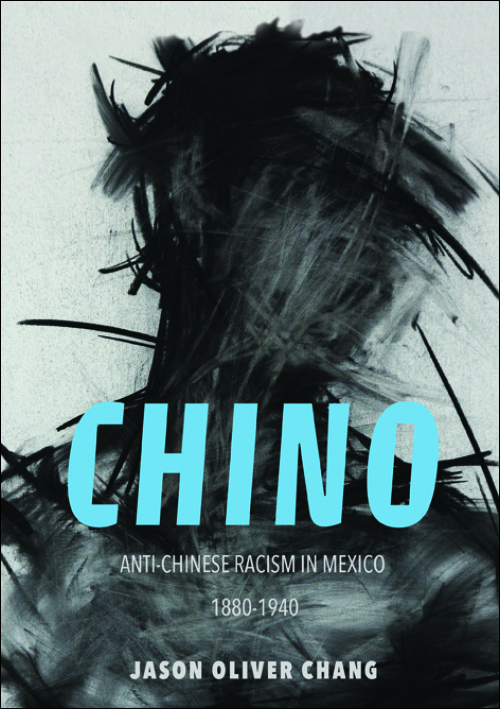

Yet even the bloodiest revolution has its icons. Mexico’s quintessential revolutionaries, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata, have become so recognizable today that it’s easy to take their politics at face-value and romanticize what they fought for. Jason Oliver Chang, an assistant professor at the University of Connecticut, wants to change that. Speaking in late May at the Museum of Chinese in America, he gave a lecture prepared from his most recently published book, Chino: Anti-Chinese Racism in Mexico, 1880-1940.

Uncovering the forgotten history of anti-Chinese propaganda and violence documented in the years around the revolution, the book reads like a dossier of state secrets. In one chilling example, you’ll read how Pancho Villa gave orders to execute 60 Chinese prisoners by throwing them down a mineshaft. Magonistas, along with many other revolutionary parties on the left and right, used antichinismo — anti-Chinese rhetoric and policy making — to popularize their own movements. But those incidents pale in comparison to the massacre that occurred in Torreón, Coahuila, during one of the first battles of the revolution. There, 303 Chinese men, women, and children were killed — some even butchered — by both civilians and soldiers, marking the bloodiest incident of anti-Chinese violence ever recorded in the Americas…

Read the entire article here.