Bewildered in Boston

HiLobrow

2011-11-12

Joshua Glenn, Co-Founder & Editor-in-Chief

Fanny Howe isn’t part of the local literary canon. But her seven novels about interracial love and utopian dreaming offer a rich social history of Boston in the 1960s and ’70s.

[This essay first appeared in The Boston Globe’s IDEAS section, on March 7, 2004.]

Fanny Howe isn’t wild about her hometown. “Boston is a parochial and paranoid city,” the 63-year-old poet and novelist charges in the introduction to The Wedding Dress (University of California), a new collection of her literary essays. “It doesn’t admit its own defects, and it belittles its own children as a result.”

Between 1968 and 1987 the Cambridge-born Howe lectured at Tufts, MIT, and other local institutions while publishing 19 books of poetry and fiction, including a series of seven semi-autobiographical novels obsessively chronicling not just particular Boston neighborhoods but the social, economic, and political tensions that plagued the city in the racially charged ’60s and ’70s. Yet it wasn’t until the University of California at San Diego offered her tenure in ’87 that Howe began to be recognized as one of the country’s least compromising yet most readable experimentalist writers. Since then, she has won the National Poetry Foundation Award, the Pushcart Prize for fiction, and the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize from the Academy of American Poets, among other prestigious awards.

Still, she’s never been celebrated as part of Boston’s literary pantheon. “This city is tougher on its own—that’s a sign of its provincialism,” says Howe’s old friend Bill Corbett, an influential local poet and writer-in-residence at MIT. “Fanny had to leave town in order to find her audience.”

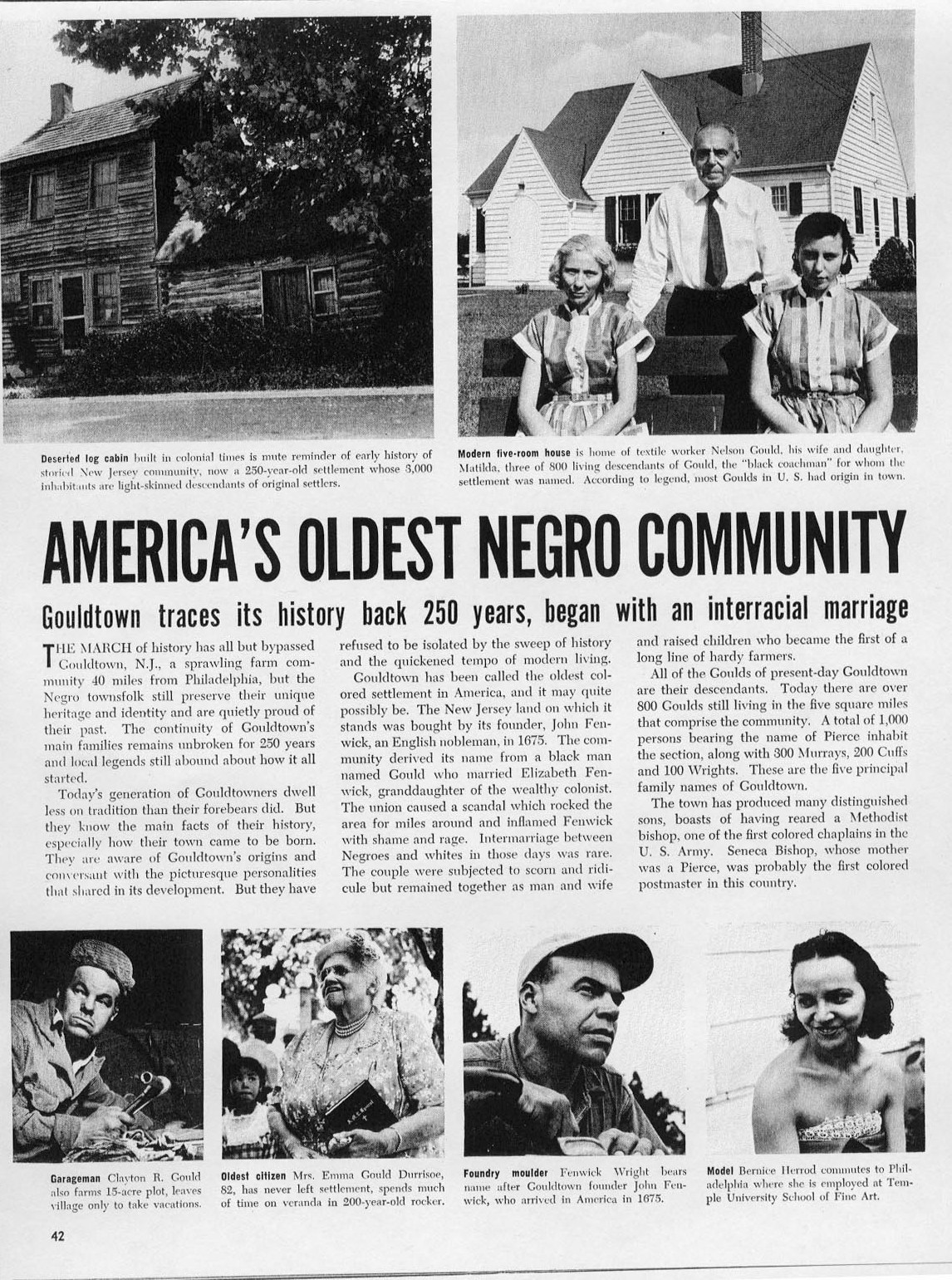

But Howe says Boston’s reluctance to recognize her work was the least of her worries. In The Wedding Dress, she recounts her experiences as a well-born Brahmin turned community activist, a white woman married to a person of color, and a mother of three mixed-race children during the city’s violent busing crisis—and recalls feeling that she’d never be the same again. “[The late anti-busing activist] Louise Day Hicks and the vociferous Boston Irish were like the dogs and hoses in the South…,” she writes. “Some worldview was inexorably shifting in me.”

Her daughter Danzy Senna, whose bestselling 1998 novel Caucasia drew upon her own memories of growing up in Boston in the early ’70s, says Howe “had an epiphany: As the mother of nonwhite children, she was no longer comfortable in the blind spot of the white world. She became a race traitor and a keen analyst of whiteness, in all its complacency and complicity.” As Howe herself writes in The Wedding Dress, she often feels “that my skin is white but my soul is not, and that I am in camouflage.”…

..It was an era of assassinations and race riots, and Boston’s black neighborhoods, where the newlyweds spent their time, sometimes became war zones. (“My white face felt like something I had foolishly chosen to wear to the wrong place,” recalls Henny, protagonist of Indivisible, the last of Howe’s memoiristic novels, of her travels “from Connolly’s to Bob the Chef to Joyce Chen’s and the Heath Street projects.”) Still, Howe and Senna bought a crumbling Victorian on Robeson Street in Jamaica Plain, and quixotically tried to establish their own racially neutral utopia. Senna went to work for Beacon Press, while Howe lectured at Tufts, got involved in neighborhood politics, and filled the house with “Carl’s family and Jamaican, Irish, and African friends of friends,” as she puts it.

The couple had three children—daughters Ann Lucien and Danzy, and son Maceo—in four years. Danzy looked white, but Howe encouraged all three children to think of themselves as black, and enrolled them in Roxbury public schools and the late Elma Lewis’s arts programs. (The white mother in Senna’s Caucasia tells her mixed-race daughter, “It doesn’t matter what your color is or where you’re born into, you know? It matters who you choose to call your own.”)

But as Howe admits, “Boston was a poor choice of a place to live” for a mixed-race family. “Many times people stopped me with my children, to ask, ‘Are they yours?’ with an expression of disgust and disbelief on their faces.” In a 1985 poem titled “Robeson Street,” she’d recall: “This stage was really hell — the fracas of an el/to downtown Boston, back out again,/with white boys banging the lids of garbage cans,/calling racial zingers into our artificial lights.”…

Read the entire article here.