White people have been passing for black for centuries. A historian explains.Posted in Articles, History, Interviews, Media Archive, Passing, United States on 2015-06-17 21:32Z by Steven |

White people have been passing for black for centuries. A historian explains.

Vox

2015-06-15

Dara Lind, Jetpack Comandante

The story of Rachel Dolezal — the now-former Spokane NAACP president whose parents have claimed she’s white — has opened up an enormously complicated debate about race and identity in general, and blackness in America in particular.

Dolezal has presented herself as “black, white, and American Indian/Alaskan Native,” but her estranged parents say she’s simply white and has been trying to deceive everyone. When the scandal attracted national attention, Dolezal resigned from her NAACP presidency — without saying anything about her race.

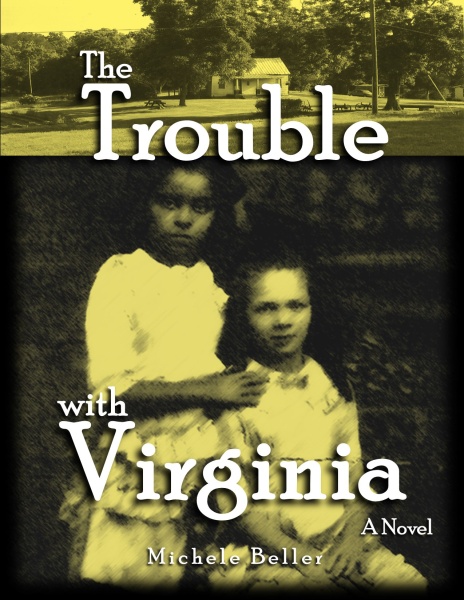

Examples of white people passing as black are much less common than the reverse, but there’s still historical precedent for what Dolezal did. Baz Dreisinger, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, traced the history of white passing in a 2008 book called Near Black. I talked to Dreisinger about how white passing has worked over time, and asked her whether there is ever a legitimate way to “cross-identify” with black culture.

Dara Lind: Can you give us a brief rundown of the history of white people passing as black in America?

Baz Dreisinger: It’s not like this was a massive chapter in American history, like traditional racial passing, which is a massive chapter. But I think people are shocked to discover that there is actually this history of white people who’ve passed as black and that Rachel Dolezal is hardly the first person to come along and do it, and in fact the way that she did it is in line with a number of historical examples.

In the context of slavery, there are both real and fictional accounts of white people who became enslaved — sometimes white people from the North who are kidnapped and sold into slavery as black. In a sense, passing for black becomes secondary to passing for slave. The idea is that the economic basis of this trumps the racial basis — not that they’re separate.

In that context, obviously, there was no change of appearance necessary. But in the 20th century, there’s a technology of passing that has to happen in order for the passing to be successful. Some people dyed their skin black and passed as black — the most famous example of that is John Howard Griffin, who wrote a memoir of his experience passing for a black man in the South during the era of Jim Crow. It’s called Black Like Me. He did it for a temporary experiment; he literally sat under the sun lamp and darkened his skin in order to do that. And there’s a woman who did a similar experiment to Griffin, whose name was Grace Halsell, who actually spent much of her life doing experimental passings — she passed as Native American, she passed as working-class — in order again to write exposés about what it’s like to be those things. So she wrote a memoir in the ’60s called Soul Sister, where she went through the same experiment Griffin did, only 10 years later, she’s in the North in Harlem as well as in the South, and her whole concept was, “I want to see what it’s like as a woman to do this.”

I think music is the most powerful place where we’ve seen this sort of passing happen, and also cultural appropriation — in many ways, my book is as much about cultural appropriation as it is about passing. You have a character like Eminem who’s clearly not passing, but is bringing up all these questions about cultural ownership and cross-racial identification — what does it mean to own a culture? Is there such a thing as owning a culture? Passing is a difficult thing to do today, given the legacies of cultural appropriation, of the metaphorical ripping off of black culture that we’ve seen — and, especially in music, appropriation where there’s literally not a credit being given and also not financial remuneration being given for cultural products that were inventions of nonwhite people…

Read the entire interview here.