Lesec, from Brave Mulato into Blackness?: Defection to France and Spanish Racial RegressionPosted in Articles, Caribbean/Latin America, History, Media Archive, Slavery on 2018-04-04 02:33Z by Steven |

Lesec, from Brave Mulato into Blackness?: Defection to France and Spanish Racial Regression

Age of Revolutions

2018-04-02

Charlton W. Yingling, Assistant Professor of History

University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky

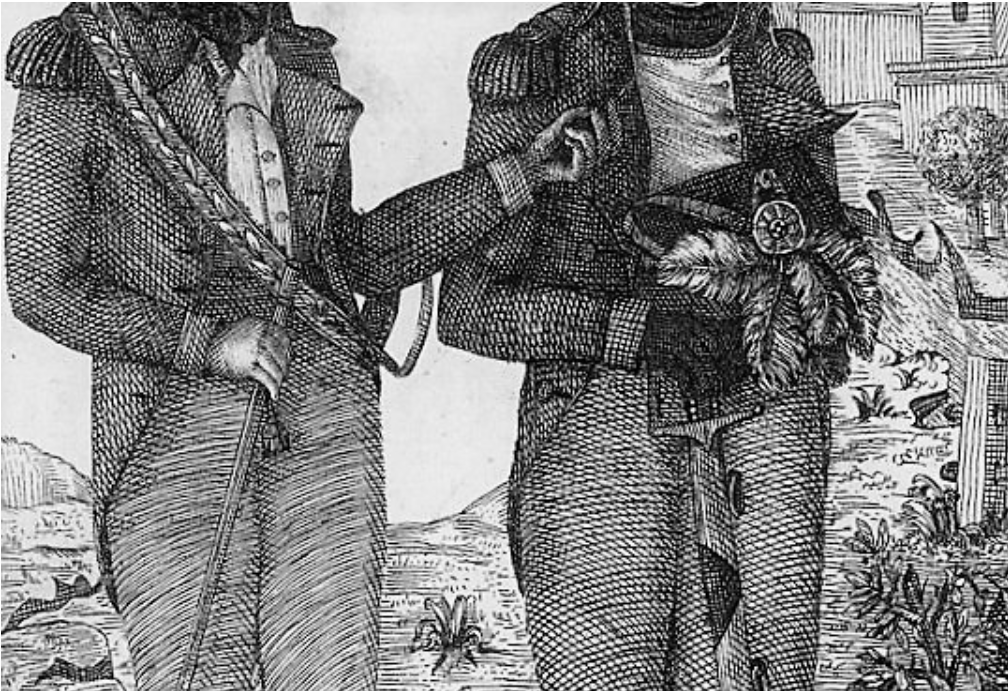

In May 1794, Governor Joaquín García of Spanish Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) praised the “brave spirit” of “Carlos Gabriel Lesec, mulato,” a term denoting European and African heritage. As an officer in Spain’s Black Auxiliaries, Lesec had just repulsed troops of the French Republic in a resounding victory at Santa Susana on the border with Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti). As the third anniversary of the Haitian Revolution approached, thousands of ex-slaves had expanded their liberatory war under Spanish flags and occupied nearly half of Saint-Domingue.[1] These “Black Auxiliaries” of Spain enjoyed limited manumissions and material support in their war against the French, their former exploiters. Their leaders, Jean-François and Georges Biassou, represented some of the earliest participants in the initial slave revolts of 1791. Those who ascended later, such as Toussaint Louverture and his officer Charles Lesec, seized a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity at upward mobility by punishing their former French oppressors. Despite these victories, García was dismayed by the “disunion that reigns between the black chiefs Biassou and Toussaint,” who along with Jean-François were Lesec’s superiors.[2] Six months earlier French commissioner Léger-Félicité Sonthonax had begun tactical, practical emancipations, in part to attract black supporters due to desperation over his opponents’ successes…

Read the entire article here.