The African American Experience in Antebellum Cabell County, Virginia/West Virginia, 1810-1865Posted in Articles, History, Media Archive, Slavery, United States, Virginia on 2013-04-05 17:41Z by Steven |

The African American Experience in Antebellum Cabell County, Virginia/West Virginia, 1810-1865

Ohio Valley History

Filson Historical Society

Volume 11, Number 3, Fall 2011

pages 3-23

Cicero M. Fain III, Assistant Professor of History

College of Southern Maryland

Located on the Ohio River in western Virginia, adjacent to southeastern Ohio and eastern Kentucky, antebellum Cabell County lay at the fulcrum of east and west, north and south, freedom and slavery. Possessed of a bountiful countryside—replete with wildlife, timber, pristine streams and creeks, and rich river-bottom soil along the navigable Ohio and Guyandotte rivers—it held great potential for settlers who sought to put down roots. Drawn by its promising location and cheap, arable land, migrants settled in the county in increasing numbers in the early 1800s, and many settlers took their slaves with them. Yet like most counties on Virginia’s western border, antebellum Cabell County was, in historian Ira Berlin’s words, a “society with slaves” rather than a “slave society.” In contrast to the rice and cotton-growing regions of the Deep South where the institution of slavery shaped the political economy and “the master-slave relationship provided the model for all social relations,” slavery never became central to the economy or social structure of Cabell County. Unlike Kanawha County, Virginia, to the northeast (and from which it was formed in 1809), Cabell County lacked industrial slavery. Unlike Jefferson County in the lower Shenandoah Valley, it lacked the numbers to support plantation slavery. Distant from plantation society and the rigid social and cultural norms imposed by the planter elite of eastern Virginia, Cabell County reveals the significance of slavery even within a “society with slaves” like central Appalachia, the impact of western expansion on slavery, and the hardening of racial attitudes in the Ohio Valley. Equally important, the county’s antebellum history helps illuminate the ways in which African Americans living in this border region exercised agency in order to better their condition.

By 1810, almost three thousand people resided in Cabell County, including 221 slaves and twenty-five Indians, or as one local historian notes, “about 1½ persons to the square mile.” In the county’s early years, it had only two villages of note. Guyandotte, formed in 1810 at the confluence of the Guyandotte and Ohio rivers, featured a number of businesses and a small but growing port. By the early 1830s, the town hosted many river travelers and benefitted from the construction of a road that connected it to the James River and Kanawha Turnpike at Barboursville, the county seat. Formed in 1813 and situated south of Guyandotte along the Guyandotte River, Barboursville was surrounded by large expanses of fertile land and plentiful timber. Farming and manufacturing formed the economic foundation of the village in its formative years. Increasing settlement in and near Guyandotte and Barboursville in the eastern part of the county close to the turnpike sparked economic growth throughout the early 1800s…

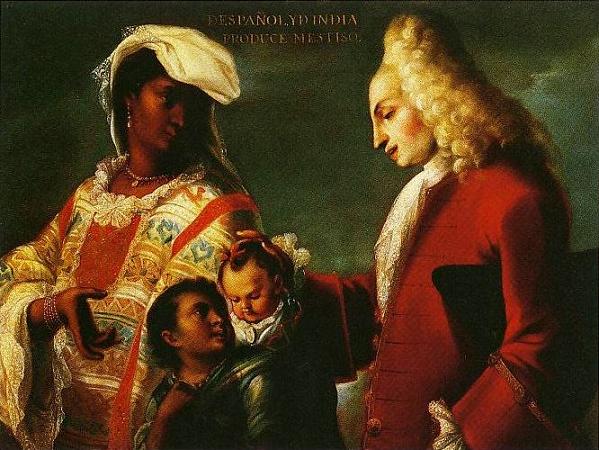

…Following a longstanding trend, black female slaves outnumbered black male slaves in Cabell County, an imbalance that still existed after emancipation and when black migrants began arriving in the early 1870s. Slaveholders favored female slaves in part because they (along with male slaves younger than twelve) were not taxed. Four other factors help explain the gender imbalance among Cabell County’s enslaved population. Female slaves cost less than enslaved men, slave children inherited the status of their mothers, and enslaved men were more able and thus more likely run away. In addition, in a society of slaves where slave ownership was more a status symbol than an economic necessity, many slaveholders employed enslaved women who worked as domestics. In 1860, Cabell County’s enslaved population was also quite young, with 30 percent (ninety three) of the county’s slaves nine or younger. Slaves under the age of twenty constituted 57 percent of the county’s total (ninety-five females and eighty males). Most striking, those under thirty represented 74 percent of the county’s enslaved population, with 121 females and 105 males (226 total) in this category. Cabell County’s black population was also growing lighter in skin color. In 1860, black slaves outnumbered mulattoes 215 to ninety (70.5 percent to 29.5 percent), but the county’s mulatto population was growing faster. Of the 136 males, ninety five (70 percent) were black and forty one (30 percent) mulatto. Of the 169 females, 120 (71 percent) were black and forty nine (29 percent) mulatto. Reflecting broader trends, the county’s mulatto population was concentrated among the young as increasing numbers of mulatto parents produced greater numbers of mulatto children…

…While the county’s enslaved mulatto population comprised 29.5 percent of the slave population, the county’s free mulatto population comprised 42 percent (ten of twenty four) of the total free black population. Most lived in the county’s more populated districts. Five resided in Guyandotte Post Office, two each lived in Barboursville and Guyandotte townships, and one lived in Cabell Court House. All six free blacks residing in white households were mulatto. The 1860 census also reveals that more free black females lived in Cabell County than free black males, but the gender imbalance exceeded that within the slave population. While female slaves comprised 55.4 percent of the general slave population in 1860, free black females, assisted by the eight women in the Haley family, comprised 62.5 percent (fifteen of twenty four) of the county’s free black population. These fifteen resided in seven households, just over two per household, though removing the Haley women from the calculation results in an average of slightly more than one black female per household. The county’s free black population was also disproportionally older, with 59 percent aged thirty and above…

Read the entire article here.